Ever wondered how to tell good carbs from bad? These measures can help reveal how quickly foods can raise your blood sugar.

What Experts Need You to Know About the Glycemic Index Vs. Glycemic Load

By now, we all know about good carbs and bad carbs. The good ones—like whole grains, vegetables, and legumes—are minimally processed and loaded with nutrients. The bad ones—found in white bread, white pasta, white rice—cause major spikes in blood sugar, leading to the kind of crashes that trigger cravings for more high-carb foods. But what about the many carbs in between? It can be downright tricky pinpointing whether some of them are “good” or “bad.” That’s where the glycemic index (GI) comes into play.

“The glycemic index is based on a system where foods are ranked zero to 100 according to how drastically they cause blood sugar to rise,” says Vandana Sheth, RDN, CDCES, a Los Angeles-based spokesperson for the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists. “Foods with higher fiber, protein, and fat tend to have a lower glycemic index, as they take longer to break down and they lead to a smaller spike in blood sugar. The more processed foods usually have a higher glycemic index.”

Glycemic index

The GI has been around since 1981, when nutrition scientist David Jenkins, MD, PhD, set out to determine which carbs are best and which are worst. First, he had to come up with a way to measure a food’s effect on blood sugar.

In a study, published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Dr. Jenkins and a team of researchers enlisted a group of healthy volunteers and asked them to eat a variety of common foods, each of which contained 50 grams of carbohydrate. The researchers then measured the participants’ blood sugar over the two hours that followed.

The results were surprising. Almost everyone assumed that table sugar would be the worst offender, certainly worse than the complex carbohydrates found in starchy staples such as rice and bread. But this didn’t always prove true. Some starchy foods, like potatoes and cornflakes, ranked very high on the index, raising blood sugar nearly as much as pure glucose.

Where the glycemic index fell short

Something was clearly wrong. The results seemed to demonize healthy foods, such as carrots and strawberries. Watermelon was practically off the top of the GI chart. But no one ever gained weight from eating carrots. Nor do carrots, in the real world, raise blood sugar. What was the GI missing?

The GI measures the effects of a standard amount of carbohydrate: 50 grams, or about 1 1/2 ounces. But you’d have to eat seven or eight large carrots to get 50 grams of carbohydrate. The same holds true for most vegetables and fruits. They’re full of water, so there’s not much room in them for carbohydrates. Bread, on the other hand, is crammed with carbohydrates. One large slice has 48 grams of total carb.

That wasn’t the only problem. “The glycemic index rating applies only when the food is consumed on an empty stomach” without any other type of food, says Sheth. That isn’t exactly the way most people eat. And it explains why the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics considers the glycemic index an imperfect, though useful tool in identifying lower-glycemic foods.

Glycemic load

To solve the discrepancy, scientists came up with another measurement: glycemic load (GL). The GL takes into account not only the type of carbohydrate in a given food, but also the amount of carb you’d eat in a standard serving.

To get the GL of a food, the carb content of the actual serving is multiplied by the food’s GI. That number is then divided by 100. For example: To get the GL for beets, you’d multiply 13 (the carb content) by 64 (the GI). You’d then divide 832 (the total) by 100 to get a GL of 8.3.

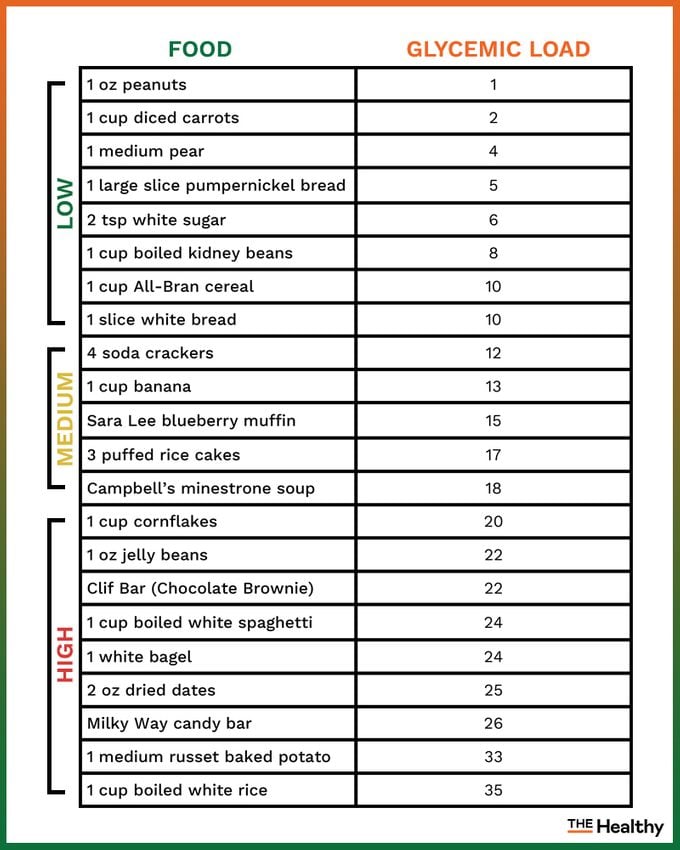

A GL above 20 is considered high, between 11 and 19 is moderate, and 10 or less is considered low.

This made more sense. By this criterion, carrots, strawberries, and other low-calorie foods—like beets—are clearly good to eat. They all have low GL values, since the amount of carbohydrate they contain is low.

Glycemic load is better, but…

The GL has turned out to be a powerful way to think about not just individual foods, but also whole meals and even entire diets. It may even have an effect on disease risk, though the research is inconclusive.

Some studies suggest that the higher the GL, the greater the incidence of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. A review of research published in the journal Diabetes Care, for instance, suggests that a diet built on high-GL foods can raise your risk for type 2 diabetes. A large study, published in 2020 in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, suggests the same risk for coronary heart disease.

On the other hand, a review of studies published in 2019, also in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, shows no significant association between GI or GL and all-cause mortality in men—but it does in women.

No wonder the nutrition community is still debating how much relevance to give the GI and GL.”When it comes to food choices, the more knowledge you have, the more informed decisions you can make,” says Sheth. “I recommend that clients focus more on carbohydrate portions, timing, and foods higher in fiber. Depending on their interest and motivation, we will then discuss glycemic index and glycemic load.” You can get a sense of how foods rank by checking out this glycemic load chart.