This Doctor Is Saving Limbs in Black Patients with Diabetes

Updated: Oct. 11, 2022

Black patients lose limbs to diabetes at three times the rate that others do. One doctor is on a mission to spare them this unjust fate.

Saving Henry’s last leg

It was a Friday evening in the hospital after a particularly grueling week when Foluso Fakorede, MD, the only cardiologist in Bolivar County, Mississippi, walked into room 336. Henry Dotstry lay on a cot, his gray curls puffed on a pillow. Dr. Fakorede smelled the circumstances—a rancid whiff, like dead mice. He asked a nurse to undress the wound on Henry’s left foot and then slipped on nitrile gloves to examine the damage. Henry’s calf had swelled to nearly the size of his thigh. The tops of his toes were dark; his sole was yellow, oozing. Dr. Fakorede’s gut clenched. It’s rotten, he thought.

He peeled off his gloves and read over Henry’s chart: He was 67, had never smoked. His ultrasound results showed that the circulation in his leg was poor. Uncontrolled diabetes, it seemed, had constricted the blood flow to his foot, and without it, the infection would not heal. A surgeon had typed up his recommendation. It began: “Mr. Dotstry has limited options.”

Dr. Fakorede scanned the room. He has quick, piercing eyes, a shaved head, and, at 38, the frame of an amateur bodybuilder. Henry was still. His mouth arched downward, and faint eyebrows sat high above his lids, giving him a look of disbelief. Next to his cot stood a flesh-colored prosthesis, balancing in a black sneaker.

“How’d you lose that other leg?” Dr. Fakorede asked. Henry was tired, and a stroke had slowed his recall. Diabetes had recently taken his right leg, below the knee. An amputation of his left would leave him in a wheelchair.

Dr. Fakorede explained that he wasn’t the kind of doctor who cuts. He was there because he could test circulation, get blood flowing, and try to prevent any amputation that wasn’t necessary. He hated that doctors hadn’t screened Henry earlier—when he’d had the stroke or lost his leg. “Your legs are twins,” he said. “What happens in one happens in the other.”

Henry’s foot was decaying—fast

Henry needed an immediate angiogram, an imaging test that would show blockages in his arteries. He also needed a revascularization procedure to clean them out, with a thin catheter that shaves plaque and tiny balloons to widen blood vessels. His foot was decaying, fast. Dr. Fakorede had grown obsessed with legs, infuriated by the toll of amputations on African Americans. His billboards on Highway 61, running up the Mississippi Delta, announced his ambitions: “Amputation Prevention Institute.”

People with diabetes undergo 130,000 amputations each year. Often these amputees are from low-income and underinsured neighborhoods, and Black patients lose limbs at a rate triple that of others. About 34 million people in America have diabetes, and Mississippi has some of the highest rates. The vast majority have type 2; their bodies resist insulin or their pancreases don’t produce enough, making their blood sugar levels rise.

Genetics plays a role in the condition, but so do obesity and nutrition: High-fat meals, sugary foods, and not enough fiber, along with little exercise, amplify the risk. Poverty can double the odds of developing diabetes, and it also dictates the chances of an amputation. One major study mapped diabetic amputations across California, and it found that the lowest-income neighborhoods had amputation rates ten times higher than the richest.

From Nigeria to Mississippi

Dr. Fakorede, who was born in Nigeria and moved to New Jersey as a teenager, came to practice in Mississippi five years ago. But he has spent years studying health disparities. African Americans develop chronic diseases a decade earlier than their White counterparts; they are twice as likely to die from diabetes; and they live, on average, three years fewer. A growing body of evidence shows how racial biases throughout the medical system mean worse results for African Americans. Research also shows that Black patients are more responsive to, and more trustful of, Black doctors.

Dr. Fakorede fantasized about building a cardiovascular institute and recruiting a multidisciplinary team, from electrophysiologists to podiatrists. But as he researched what it would take, he found a major barrier: a shortage of doctors in the Delta. Though Bolivar County was at the center of a diabetes epidemic, there wasn’t a single diabetes specialist—an endocrinologist—within 100 miles.

This is what uncontrolled diabetes does to your body: Without enough insulin, or when your cells can’t use it properly, sugar courses through your bloodstream. Plaque builds up faster in your vessels’ walls, slowing the blood moving to your eyes and ankles and toes. Blindness can follow, or dead tissue. Many can’t feel the pain of blood-starved limbs; the condition destroys nerves. If arteries close in the neck, it can cause a stroke. If they close in the heart, a heart attack. And if they close in the legs, gangrene.

Bolivar Medical Center, the local hospital, credentialed Dr. Fakorede, allowing him to consult on cases and do procedures in their facilities. His most complicated patients come in through the emergency room. Some arrive without any inkling that they have gangrene. One had maggots burrowing in sores. Another showed up after noticing his dog eating the dead flesh off the tips of his toes. Dr. Fakorede took a photo to add to his collection. “It was a public health crisis,” he says. “And no one was talking about amputations and the fact that what was happening was criminal.”

A long history of discrimination

For decades, African Americans in the South struggled to find and afford health care. The American Medical Association excluded Black doctors, as did its constituent societies. Some hospitals admitted Black patients through back doors and housed them in hot, crowded basements. Many required them to bring their own sheets and spoons, or even nurses. Before federal law mandated emergency services for all, hospitals regularly turned away African Americans, some in their final moments of life.

In 2015, when Dr. Fakorede moved to Mississippi, the state had the nation’s lowest number of physicians per capita. It had not expanded Medicaid to include the working poor. Across the country, 15 percent of African Americans were still uninsured, compared with 9 percent of White Americans.

Vascular disease presents a special challenge. The Affordable Care Act mandates that insurers cover all primary care screenings that are recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of preventive-care experts. The group, though, had not recommended testing anybody without symptoms, even the people most likely to develop vascular disease—older adults with diabetes, for example, or smokers. (Up to 50 percent of people who have the disease are believed to be asymptomatic.)

Paid to operate

General surgeons have a financial incentive to amputate; they don’t get paid to operate if they recommend saving a limb. And many hospitals don’t direct doctors to order angiograms, the most reliable imaging to show whether and precisely where blood flow is blocked, giving the clearest picture of whether an amputation is necessary and how much needs to be cut. Insurers don’t require the imaging either. To Dr. Fakorede, this was like removing a woman’s breast after she felt a lump without first ordering a mammogram.

He was determined to make sure that no one else lost a limb before getting the test. This wasn’t a controversial view: The professional guidelines for vascular specialists—both surgeons and cardiologists—recommend imaging of the arteries before cutting, though many surgeons argue that in emergencies, noninvasive tests such as ultrasounds are enough. Marie Gerhard-Herman, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, chaired the committee on guidelines for the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. She says that angiography before amputation “was a view that some of us thought was so obvious that it didn’t need to be stated.

“But then I saw that there were pockets of the country where no one was getting angiograms, and it seemed to be along racial and socioeconomic lines. It made me sick to my stomach.”

Spreading the word

Patients didn’t know about vascular disease, or why their legs throbbed or their feet blackened, so Dr. Fakorede went to church. He met pastors, and he stood before a pulpit several times each month. He told the crowds that what was happening was an injustice, that they didn’t need to accept it. He told them to get screened and to get a second opinion if any surgeon wanted to cut off their limbs. In the lofty Pilgrim Rest Baptist Church in Greenville, he asked the congregation, “How many of you know someone or know of someone who’s had an amputation?” Almost everyone raised a hand.

At first, Dr. Fakorede took a confrontational approach with colleagues. Some seemed skeptical that he could prevent amputations; it’s a tall claim for a complex condition. Over time, though, Dr. Fakorede tried to rein in the arrogance. “You peel off a layer that may be composed of: I’m from up North, I know it all, you should be thankful we’re here to provide services that you probably wouldn’t get before,” he says. He picked up some southern manners. Dr. Fakorede began texting doctors photos of their patients’ feet along with X-rays of their arteries before his intervention and after. Referrals picked up, and within a year he’d seen more than 500 patients.

But Bolivar Medical Center, he learned, was turning away people who couldn’t pay a portion of their revascularization bill up front. “It’s a for-profit hospital. It’s no secret. It’s the name of the game,” Dr. Fakorede says. “But a for-profit hospital is the only game in town in one of the most underserved areas. So what happens when a patient comes in and can’t afford a procedure that’s limb salvage? They eventually lose their limbs.”

A hospital spokesperson said that last year, it gave $25 million in charity care, uncompensated care, and uninsured discounts. Asked whether it turned away patients who couldn’t pay for revascularization, she did not respond directly: “We are dedicated to providing care to all people regardless of their ability to pay.”

At $237 billion in medical costs each year, diabetes is the most expensive chronic disease in the country. One of every four health-care dollars is spent on a person with the condition. When it’s left untreated, the costs pile on. Medicare spends more than $54,000 a year for an amputee, including follow-ups, wound care, and hospitalizations. Then come the uncounted tolls: lost jobs, dependence on disability checks, relatives who sacrifice wages to help with cooking and bathing and driving.

Dr. Fakorede decided that in order to treat as many people as possible, irrespective of income or insurance, he needed to build a lab of his own.

Henry’s best hope

Last January, that lab was Henry Dotstry’s best shot. The hospital’s consulting surgeon expected to amputate his leg below the knee. He had written that because Henry’s kidneys were impaired, the contrast dye used in an angiogram would be dangerous. But Dr. Fakorede could replace the dye with a colorless gas.

After Dr. Fakorede told Henry’s family his plan, his sister, Judy Dotstry, looked over at her brother, who sat slumped over the side of the cot, a blue gown slipping off his bony shoulders. Their father had been a sharecropper, and Henry had dropped out of elementary school to help on the farm, harvesting soybeans, rice, and cotton. Of ten kids, he was the oldest boy, and he took care of the others, bringing in cash and cooking them dinner. They almost never saw a doctor. Instead, they’d relied on cod-liver oil or tea from hog hooves parched over a fire.

Henry had spent his career driving tractors, hauling crops, and plowing fields, but he wasn’t insured and still rarely saw doctors. At 60, when he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and prescribed insulin, he didn’t know how to manage the medicine properly; he had never learned to read. Insulin pumps were too expensive—more than $6,000. His blood sugar levels often dropped, and he sometimes passed out or fell on the job. Little by little, his employer cut back his duties. In 2015, he had a stroke. A year later, his right foot blackened and was amputated at the ankle. The infection kept spreading, and soon his lower leg went. He could no longer work.

Two of his sisters had died from complications of diabetes. Judy had stood over their beds just as she was now standing over Henry’s. He’s still here, she reminded herself.

She crossed her arms. “He’ll be all right if they don’t have to amputate that leg,” she said.

Discrimination persists

About every five years, the doctors and researchers who make up the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reassess their screening guidelines. In 2018, the members returned to peripheral artery disease and the blood flow tests that Dr. Fakorede had asked local doctors to conduct. Once again, the panel declined to endorse them.

In its statement, the panel acknowledged that public commenters had raised concerns that the disease “is disproportionately higher among racial/ethnic minorities and low-socioeconomic populations” and that this recommendation “could perpetuate disparities in treatment and outcomes.” The panel said it needed better evidence. But as the National Institutes of Health has found, minorities in America make up less than 10 percent of patients in clinical trials.

Joshua Beckman, MD, director of vascular medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, was an expert reviewer for the task force, and its report struck him as irresponsible. It hardly noted the advantages of treatment after screening; the benefits were right there in the data. The panel discounted the strongest study, a randomized control trial, which demonstrated that vascular screening reduced mortality and days in the hospital for men ages 65 to 74. (The study bundled peripheral artery disease screening with two other tests, but in Dr. Beckman’s eyes, the outcomes remained significant.)

He was confused about why the task force had published its evaluation of screening the general public when it was clear that the condition affects specific populations. Guidelines from several American and European professional societies recommended screening people with a higher risk. “You wouldn’t test a 25-year-old for breast cancer,” Dr. Beckman says. “Screening is targeted for the group of women who are likely to get it.”

Prevention is crucial

Vascular surgeons who study limb salvage have come to see preventive care as perhaps more important than their own last-ditch efforts to open blood vessels. Philip Goodney, MD, a vascular surgeon at Dartmouth and White River Junction VA Medical Center, made a name for himself with research that showed how the regions with the lowest levels of revascularization, such as the Delta, also had the highest rates of amputation.

But revascularizations aren’t silver bullets; patients still must manage their health to keep vessels open. Dr. Goodney believes his energy is better spent studying preventive measures, such as blood sugar testing, foot checks, and vascular screening. Many patients have mild or moderate disease and can be treated with medicine and counseled to quit nicotine, to exercise, and to watch their diet.

“We need to build a health system that supports people when they are at risk, when they are doing better, and when they can keep the risk from coming back,” he says. “And where there’s a hot spot, that’s where we need to focus.”

Dr. Fakorede, along with the Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease Caucus, is pushing for the task force to reevaluate the evidence on screening at-risk patients, for federal insurers to start an amputation-prevention program, and for Medicare to ensure that no amputation is allowed before evaluating arteries. Other groups are advocating for legislation that would require hospitals to publicly report their amputation rates.

By early 2020, Dr. Fakorede had seen more than 10,000 cardiovascular patients from around the Delta. He was performing about 500 angiograms annually. Last year, he published a paper in Cath Lab Digest describing an 88 percent decrease in major amputations at Bolivar Medical Center, from 56 to 7. The hospital has different internal figures, which also reflect a significant decrease: Between 2014 and 2017, the hospital recorded that major amputations had fallen 75 percent—from 24 to six.

A beautiful Sunday

Under a crisp wide sky, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, churches around town were opening their doors for services. Dr. Fakorede’s office was scheduled to be closed, but he’d called in his nurses and radiology technicians to staff Henry Dotstry’s case.

“What’s up, young man?” Dr. Fakorede greeted Henry, who was fading into his Ambien, and then he handed Judy a diagram of a leg. “The prayer is that we can find this many vessels to open up,” he said. “As soon as I’m done, I’ll let you know what I find.”

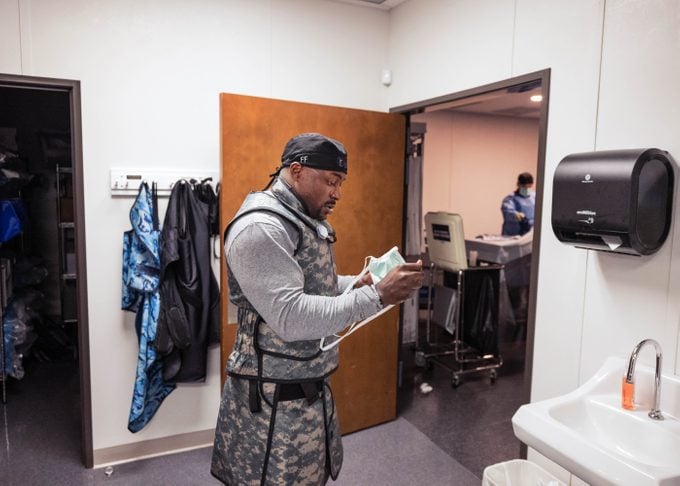

In the procedure room, he put on his camouflage-patterned lead apron, and with an assistant, he inserted an IV near Henry’s waist. He wound a wire across Henry’s iliac artery, into the top of the left leg. The femoral artery was open, even though it had hardened around the edges, a common complication of diabetes. They shot a gas down the arteries in Henry’s lower leg so the X-ray could capture its flow.

Dr. Fakorede looped his thumbs into the top of his vest, waiting for the image. Other than a small obstruction, circulation to the toes was good. “They don’t need to whack off the knee,” he said, staring at the screen. Henry would lose one toe.

After they’d cleaned out the plaque, Dr. Fakorede called Judy into the lab and showed her a playback of the blood moving through Henry’s vessels. She could tell that his foot had enough flow.

She folded over, running her palms along her thighs. “Y’all have done a miracle, Jesus.”

Henry would need wound care, help controlling his sugars, and a month in rehab. Judy and her daughter would have to learn to manage his antibiotics and find him an apartment. He’d still be able to tinker with his cars, as he did most afternoons.

Dr. Fakorede scrubbed out. He sat at his desk to update Henry’s doctors. He dialed the hospital, asked for one of the nurses, and explained what he’d found: Henry didn’t need a leg amputation.

“Oh, great,” the nurse replied. “The surgeon was calling and asking about that. He called and tried to schedule one.”

Dr. Fakorede had been typing up notes at the same time, but now he stopped. “He was trying to schedule it when?” he asked.

“He was trying to schedule it today.”